AN ETHICAL APPROACH

A talk delivered by

Tom Flynn in Stockholm on April 25 to the Swedish Committee for the Reunification

of the Parthenon Marbles.

Good afternoon. First of

all thank you to Krister (Kumlin) for being so kind as to invite me to Stockholm

to speak to you. This is my first visit to Sweden and I feel very honoured

that what brings me here is our shared desire to achieve the reunification

of the Parthenon Marbles in Athens.

This afternoon I'd like to offer some thoughts on the ethics of the reunification

campaign, as I see it, and why I believe we need to reconnect with the

architectural significance of the Marbles.

My doctoral thesis was concerned with nineteenth-century attitudes towards

the ancient sculpture technique known as chryselephantine, meaning the

combination of gold and ivory. As you know, these were the materials used

to construct the colossal cult statue of Athena Parthenos erected inside

the ancient temple during the Periclean building programme in the fifth

century BC.

The sculptor Pheidias was responsible for the construction of that figure

as well as the temple sculptures about which we're all so concerned. Of

course, the great chryselephantine statues of antiquity no longer exist.

The last that was heard of the Athena Parthenos was her presence in Constantinople

and it is perhaps no surprise given the inherent value of the materials

from which she was constructed that she was eventually dismantled and

dispersed.

Gipsreplik av Athena Parthenos.

Foto: Inger Eriksson

The history of that ancient figure is shrouded in mystery and intrigue

- and studying its history left me curious to know what the Parthenos

might have looked like standing in the temple. This also helped sparked

my interest in the Marbles issue. We can never recover the Athena Parthenos,

but the temple in which she stood deserves to be treated with a particular

kind of respect, a respect that few if any other European cultural monuments

deserve to quite the same extent.

So, recently I've been thinking more about the ethical dimension of this

debate. This arose as a background theme during last year's cultural property

conference held at the New Acropolis Museum in Athens. There seemed to

be a general consensus that, leaving aside all the political and legal

questions, reunification is the right thing to do. Indeed that is essentially

how one might define ethics - as the adoption of the good and proper way

of acting under given circumstances. The British Museum may claim to have

legal title to the Marbles - which is by no means universally accepted

- but is their ownership of the Marbles legitimate? However, if we were

to conclude that the British Museum has acted unethically with regard

to this issue, or had not yet adopted an ethical approach to resolving

it, can we say the same about the way we have behaved on the other side?

We may believe that return is the ethical thing to do, but are we pursuing

ethical ways of bringing that about? Is our position towards the British

Museum an ethical one?

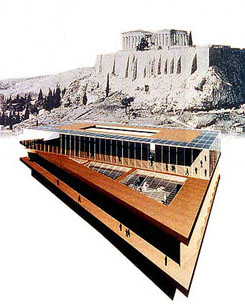

So, with the New Acropolis Museum scheduled to open in June, what options

remain open to those of us seeking the return of the Parthenon Marbles

to Athens? The two main approaches might be summarized thus: to continue

on the path of diplomacy, despite the lack of progress achieved by this

approach to date; or to revert to some form of legal action. Let us concentrate

on the second option first, that of litigation.

In the light of the British Museum's refusal to return the Marbles, or

to enter into the kind of constructive dialogue required to resolve the

issue, the suggestion has increasingly been made in recent years that

some form of lawsuit by the Greeks might offer a way out of the impasse.

Specialist cultural property lawyers have on several occasions made clear

that The British Museum Act of 1963, so frequently cited as prohibiting

the return of the Marbles, is by no means insurmountable and could be

amended at the behest of the director and trustees. Indeed were the British

Museum's trustees to vote for an amendment to the Act to allow for an

extraordinary act of deaccession applicable only to the Marbles, Parliament

would be obliged to comply, thereby paving the way for return.

However, while the law clearly offers the remote prospect of a resolution,

albeit through a potentially tortuous route, it also contains hazards.

The most obvious of these is that litigation is likely to polarize the

two sides even more than they are at present. More importantly, failure

to find an acceptable solution through law would leave the Greeks few

if any remaining options to explore. This could make a return to diplomacy

all the more embittered and time-consuming.

Thus it seems clear that the most favourable option open to Greece at

the present time is to reinforce the ethical arguments in favour of return

and to adopt a more ethical approach to how those arguments are articulated.

To that end, the British Museum should be encouraged to recognise the

numerous benefits that would issue from what would be widely viewed as

a magnanimous humanitarian gesture in the otherwise fraught realm of cultural

politics. And I stress this approach as a contrast to the attacks on the

British Museum and its director from some quarters, which do little to

advance the cause.

Neil MacGregor, the British Museum's highly capable and charismatic director,

has been striving to turn his museum into a new pro-active force in the

field of cultural diplomacy.

He seeks to show how objects can transcend politics; can build bridges

between nations; bring unity where previously there was division; foster

understanding in place of suspicion and distrust. That all sounds very

ethical. But such noble endeavours continue to be undermined by the case

of the Parthenon Marbles, which contradicts the British Museum's ethical

charter. With the New Acropolis Museum poised to open, it is now in Neil

MacGregor's gift to rectify that situation.

The majority of the British public wishes to see the Parthenon Marbles

returned to Athens. It is widely believed that this desire is echoed across

the global community. Now is the time to redouble efforts to identify

and publicize the many ways in which the British Museum's standing as

a 'world museum' would be immeasurably enhanced were it to agree to return.

forts. >>

Duveen Gallery i British Museum.

The fabled 'floodgates' argument that is so often raised, which suggests that returning the Marbles would lead to the inevitable emptying of museum collections, simply would not happen and most senior museum directors know this. Indeed an exceptional decision to return the sculptures to Athens would effectively foreclose calls to repatriate other objects since it would clarify the extent to which the Parthenon Marbles are a unique case deserving of a unique approach in the politics of cultural heritage.

The British Museum often claims that the presence of the Parthenon Marbles in Bloomsbury allows it to tell a story of humankind's finest cultural achievements and to point out the development of stylistic influences across cultures, time and geography. It maintains that this story can only be told in the context of the British Museum and that without the Parthenon Marbles the story would be seriously impaired. We know this to be a flawed argument. However, the Marbles could be returned as part of a broader project that would include the long-overdue refurbishment of the Duveen Galleries where the Marbles are so inappropriately and misleadingly situated.

First-class replicas of the Marbles could be displayed in the refurbished galleries alongside important objects loaned by Greece never before seen in London. Far from impoverishing the British Museum, this project would significantly enhance the museum's stature as a cultural destination, revealing that it puts the integrity of objects above the petty politics of ownership. This would be an ethical approach. More importantly, the British Museum's enduring ability to tell the story of cultural achievement would be revealed as in no way dependent upon the original Marbles being present.

Gudarna Poseidon, Apollo och Artemis. Parthenontemplets östra fris. Nya Akropolismuseet 2008.

Foto: Inger Eriksson

For too long, excessive emphasis has been placed on the negative implications of the British Museum's refusal to return the Parthenon Marbles. This is understandable but unconstructive. Moreover, it leads to mutual distrust and suspicion. As a result, the aesthetic and historical importance of the sculptures continues to be obscured by controversy and will continue be so unless a new approach is sought.

I believe it's now time to shift attention onto a more positive trajectory by focusing on the multiple benefits the British Museum would enjoy as a result of repatriation. By doing so it would finally have conformed to the wishes of its public in keeping with its founding charter. But more importantly, by demonstrating strong ethical and moral leadership it would show the global community that there is a way to resolve controversial and divisive cultural property issues. That in itself would be a legacy of which any director of an encyclopedic museum would be justifiably proud. Moreover, it would have the effect of improving Anglo-Greek relations on a broader front.

In summary, then, the increasingly ad hominen attacks against Mr MacGregor and the critical assaults heaped upon the British Museum are not helpful. They merely allow Neil MacGregor to claim the moral high ground. If, instead, we emphasised a means of making that moral high ground even more moral, then this might have greater impact.

Now there is another important issue that needs emphasizing and that is the architectural significance of the Marbles.

Constructed on the same axis as the ancient temple, the new gallery allows the metopes and frieze sculptures to be displayed in such a way as to be positionally faithful to their original location on the building. In effect, this initiative restores to the surviving fragments their architectural significance. The importance of this aspect of the design cannot be underestimated since it has profound implications for a universal understanding of ancient Greek architecture and for the appreciation of Pheidias's greatest achievement within the Periclean building programme.

Kopior och original av Parthenonfrisen.

Nya Akropolismuseet.

Foto: Inger Eriksson

I raise this issue because the opening of the new Museum provides an opportunity to redress the ongoing misrepresentation of the Marbles as objects of negligible architectural significance.

In 1928, three leading British classical archaeologists, John Beazley, Donald Robertson and Bernard Ashmole, pronounced the 'Elgin Marbles' as primarily works of art rather than as architectural elements, stating: "Their former decorative function as architectural ornaments, and their present educational use as illustrations of mythical and historical events in ancient Greece, are by comparison accidental and trivial interests."

One might dismiss such pronouncements as outdated were their core message not still being propagated today, most surprisingly by Neil MacGregor, who told the Financial Times, "The life of these objects [the Parthenon Marbles] as part of the story of the Parthenon is over. They can't go back to the Parthenon. They are now part of another story."

The broader political issues ever present in cultural property debates have a tendency to overshadow important historical and aesthetic considerations. With the New Acropolis Museum about to open, the present moment represents an opportunity to restore to the Marbles a core aspect of their legacy to humankind, namely their relationship to the building for which they were designed. To do so would also re-emphasize their significance as integral to Pheidias's architectural scheme, something which is being steadily erased from the cultural memory.

This is not a question of politics. It is an issue that goes to the heart of how we view our shared architectural heritage. Moreover, the will to unify for shared enjoyment one of humankind's finest cultural achievements is ever more urgent in an increasingly fragmented and atomised world.

Finally, I wandered in to the British Museum yesterday to kill a few minutes before my lunch meeting. There in the middle of the central court, was a piece of contemporary sculpture by the Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli. The piece was entitled Heech, a motif from traditional Islamic calligraphy meaning 'nothing.' According to the label, the word symbolizes the artist's ambivalence towards the past and his sense of dissatisfaction with an inadequate present. That seems a very apt note on which to close.

Thank you.

Tom Flynn

Stockholm

April 2009

Dr Tom Flynn är konstvetare och frilansjournalist

<< Tillbaka

www.svenskaparthenon.se