STOCKHOLM in April 2009

I'd like to start with a few preliminary words about the museum, based principally on my discussions at the museum with Professor Pandermalis and with Elena Korka and other staff members during the late stages of construction. Much of what I'll be saying was published in the Museums Journal so apologies if it sounds a little familiar to some of you. In the second part I'll move on to the real reason for my being here, which is to offer some thoughts on the ethics of the reunification campaign, as I see it, and why I believe we need to reconnect with the architectural significance of the Marbles.

Having overcome a string of planning objections and other obstacles, the New Acropolis Museum is finally about to open to the public in June. All the evidence suggests that it provides a stunning environment in which to view the extraordinary treasures until recently dispersed around other Athenian museums and elsewhere in the world.

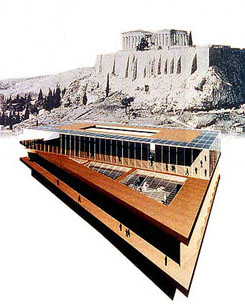

Situated at the foot of the southern slopes of the Acropolis, the new 94 million EURO complex provides a central unifying focus for the archaeological sites clustered around the monument. It also reunites numerous architectural and sculptural fragments formerly displayed in the cramped and antiquated facilities of the old Acropolis Museum built in 1874.

The new museum has successfully overcome a series of obstacles that threatened to impede its progress. Archaeological excavation of the site in the Makriyianni district directly beneath the Acropolis began in 1997 but in 2003 ran into objections from local residents who succeeded in halting progress on the building. It is a measure of the determination of the Organisation for the Construction of the New Acropolis Museum, in particular its President, the archaeologist Professor Dimitrios Pandermalis, that opposition was finally overcome and work resumed. The excavations unearthed important ruins, including private houses of the early Christian era (400-600AD), and more than 50,000 portable antiquities - sculptures, lamps, vases, coins and domestic artefacts.

Those involved with the project believe that the detractors have finally been silenced. "I don't believe there is any real controversy at the heart of this project," Professor Pandermalis told me in 2006. "True, it raised many kinds of questions. Is it the right place in which to build, for example? But why should it be negative? If it had been a private project - a hotel, a block of flats - it would have been OK. So why not a museum?"

In a recent book outlining his theory of Concept vs Context vs Content, the museum's architect Bernard Tschumi wrote of the "triple challenge" presented by the New Acropolis Museum - "How to make an architectural statement at the foot of one of the most influential buildings of all time; how to design a building on a site already occupied by extensive archaeological excavations and in an earthquake-prone region; and how to design a museum to contain an important collection of classical Greek sculptures and a singular masterpiece, the Parthenon frieze, currently still housed in the British Museum?"

Tschumi's solution appears to have succeeded on all counts. He has designed the 14,000 square meter museum to maximise the ambient natural light of the region. Using seismic technology in its foundations, which absorbs 70% of quake tremors, the building features an internal 'cella' exactly mirroring the orientation of the Parthenon, with the same number of columns as its ancient counterpart, accurate to the millimeter.

The base of the building floats on slender pillars above the 2,500 square meter archaeological site and houses the lobby, temporary exhibition space, shops and other visitor facilities. This level has been fitted with a series of glazed floor panels revealing the excavated remains beneath. The middle section, a large trapezoidal plate, accommodates the Archaic collection, other permanent galleries and a mezzanine restaurant.

The top floor climaxes with the Parthenon Gallery that contains the High Classical achievements of Periclean Athens. This floor also affords an entirely new vantage point from which to view the south side of the Acropolis and its associated monuments. The effect on reaching this upper level is a heart-stopping sense of space and light.

While the lower level is orientated in relation to the archaeological remains, the upper floors conform to the orientation of the ancient monument. In Professor Pandermalis's words, "The lower floor fits to the site and the upper floor fits to the broader environment."

The visitor is guided from level to level via a series of gentle ramps, echoing the approach to the Acropolis itself. Everywhere there are subtle reverberations of Tschumi's interlinking of concept, context and content.

It is in the upper galleries that the surviving fragments of Pheidias's Parthenon frieze and metopes will be displayed - at any rate those still in Greek hands. In stark contrast to the display in the British Museum's Duveen Galleries, the sculptures will be arranged in the New Acropolis Museum for the first time in strict relation to their original arrangement on the Parthenon, itself visible through the impressive curtain windows enveloping the building. Professor Pandermalis describes this as "a visual dialogue, a cultural platform to the Parthenon and the Acropolis."

forts. >>

Walking around the unfinished upper floors in 2006, one was aware of the series of apertures in the cella, punctuated by blank walls and windows, many of are now filled with sculptures.

Some of the door cavities represent the destruction by the Venetian mercenary army under General Morosini in 1687. The original intention was to leave vacant those spaces where the London Marbles should be located, but for some reason a decision was taken recently to fill these with replica casts of the Marbles still in London. I believe this was a mistake.

And there's the rub. Whether the finished building will help persuade the British Museum, the Louvre, and other 'encyclopaedic' museums around the world, to surrender those pieces of the Parthenon in their collections - and so 'complete' the process of unification at the heart of the Acropolis project - remains to be seen. Bernard Tschumi recently said, "As the architect of the New Acropolis Museum I remain convinced that the Parthenon Marbles will eventually be reunited in Athens." If it succeeds in this regard, the new museum could help set a new benchmark in cooperative cultural relations. But if it fails, will the museum become notable for what it does not contain rather than for what it does?

Professor Pandermalis told me in 2006 that the museum is not a shrine to absence. The gaps were intended to be an eloquent appeal for unification, to strengthen the case for the return of the pieces held in London and elsewhere. But clearly that strategy has now been revised. The Parthenon Hall makes clear the continuity between the various components.

The pieces of the frieze that remain in Athens are of very high quality so one can easily imagine how they would have been on the original building. As Professor Pandermalis told me, "In a second we can tell the story of the Parthenon Marbles as it has never been told before.

I don't know of another museum in the world where you can get all the time the feeling of the original unit of an ancient artistic complex - the opposite of the idea of a fragmentaryculture." I thought that was a particularly telling statement in the light of Neil MacGregor's persistent assertion that only in London can the world's cultural heritage be properly appreciated.

Until the London pieces return to Athens, one of the main attractions of the Parthenon Gallery will be the West Frieze, recently cleaned using cutting-edge laser technology.

When I met Dr Christina Vlassopoulou, who supervised the conservation of the West Frieze, she expressed her excitement that so many objects would finally be appreciated within the ambient natural light of the new building. They include the famous Kritios Boy, which will be one of the focal points of the new Archaic Gallery. He will be more articulate because he will be shown in context with other athletic figures such as bronzes found on the Acropolis.

You will also be able to see the back of a kore, so the new museum offers its curators opportunities to do things that were previously impossible.

Dr Vlassopoulou and her colleagues - who pioneered new techniques in conservation now being used elsewhere in the world - are still discovering fragments on the monument which relate to pieces in store or already on display. Conservation techniques have been developed to allow objects to be dismantled and reassembled to incorporate recent finds. The new museum will provide an opportunity to monitor these processes on an ongoing basis as conservation dictates and to share them with the public. This accords with Professor Pandermalis's vision of the new museum as an evolving work in progress and explains why no single grand opening was planned. Instead, the intention is to open throughout 2009.

Dr Pandermalis describes the new museum as "a museum of an archaeological site. The museum is about connecting pieces. It will be a museum in action."

Elena Korka, Director of Prehistorical and Classical Antiquities of the Archaeological Service in Athens, lived on the Makriyianni site as a child and feels a deep emotional connection with the New Acropolis Museum. About eighteen months ago, she told me she believes it could widen the debate about the 'universal museum' that has become one of the most critically contested issues in international museology. That has already started to happen.

"As a scholar and a member of the archaeological service it is a dream come true," Elena told me. "I think it's a universal museum in its own way. You don't need to have the old type of universal museum to have a universal museum; it's the message that comes out of the museum that counts. And if we follow what the British Museum has been talking about recently in terms of a new Enlightenment, well enlightenment keeps on coming from the Acropolis, from the Parthenon, it's a never-ending procedure. It's the way each society of every century grasps the message, uses it for the needs of its time, the needs of each society, so it's a universal contribution."

The old Acropolis Museum used to attract around 1.5 million people each year. The Greeks hope their New Acropolis Museum will at least double that figure. Clearly the return of the Parthenon Marbles from London would help them achieve that target.

"The life of the Parthenon Marbles as part of the story of the Parthenon is over," British Museum Director Neil MacGregor told the Financial Times in 2003. The New Acropolis Museum provides compelling evidence to the contrary.

Dr Tom Flynn is a freelance arts journalist

<< Tillbaka

www.svenskaparthenon.se